Ottoman inlaid wooden table with an Iznik ceramic tile as a table top

Once in the collection of Farouk, the last king of Egypt, this table harks from the most glorious period of Ottoman art, the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. The construction of the base is of softwood faced with a veneer of ebony with marquetry of ivory and mother of pearl. It is the product of a court workshop in Istanbul, made to order to accommodate an unusually large, 12-sided, tile from Iznik as a table top. The decoration of the woodwork and the tile are both consistent with the courtly style current during the last phase phase of Suleiman’s long reign at around 1560.

Height: 48 cm. Diameter: 61 cm

Now in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London

(Museum Number C.19-1987)

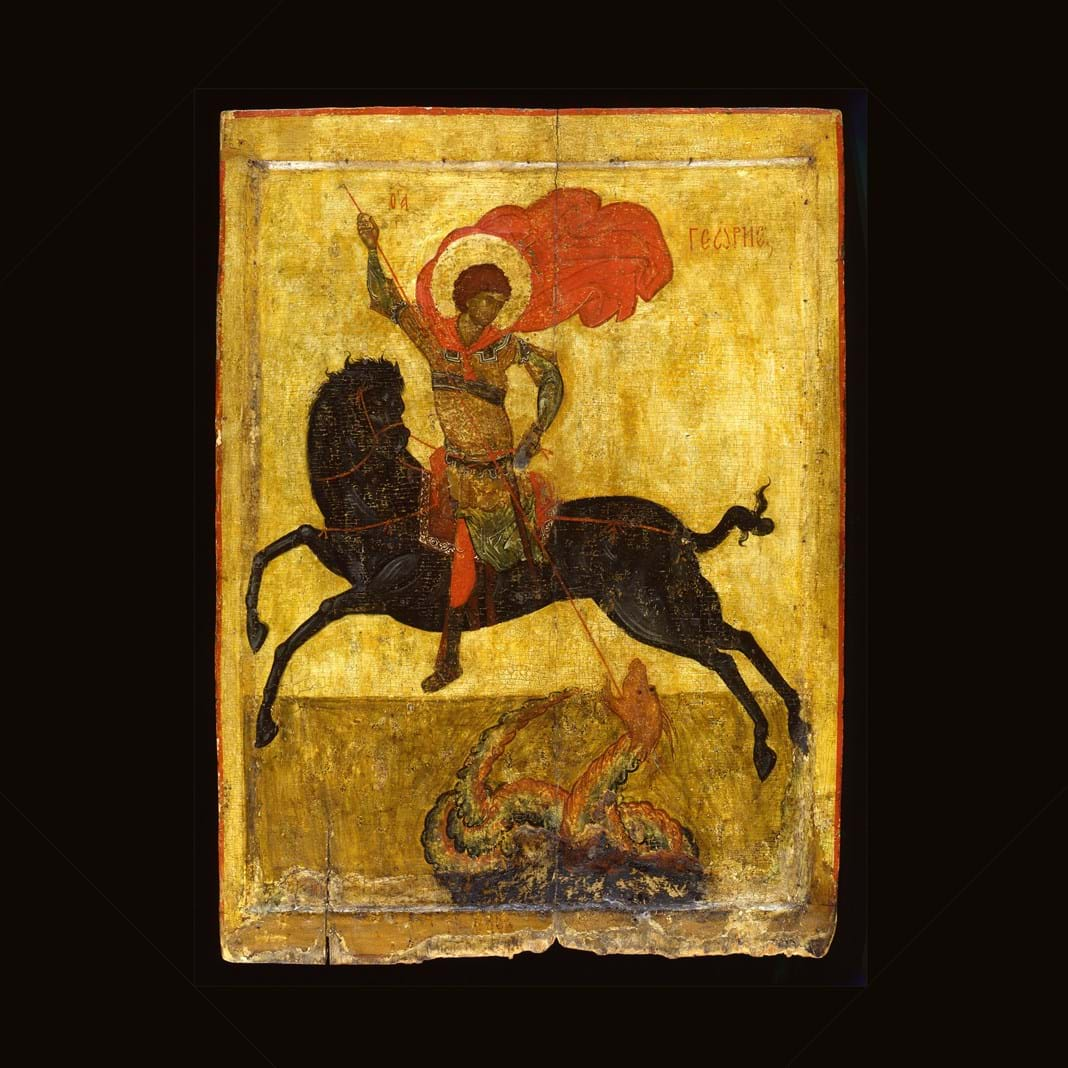

‘The Black George’ (Chernyy Georgiy)

In the eastern Mediterranean world during Late Antiquity, the image of the “Sacred Horseman” or “Holy Rider” slaying a serpent-like creature representing evil was one of the most potent talismanic symbols. Once it entered the vocabulary of Christian art, the theme was to have a long life. In it lie the origins of the representation of the mounted St George Slaying the Dragon, a subject ever popular on icons across the Orthodox world but also in Western painting.

In these, George is almost invariably shown mounted on a white charger, and it is his unusual representation here on black horse which has given this famous icon its name. One of the earliest renderings of the Miracle of St George and the Dragon on panel painting in Russia, its place of origin has been variously attributed to Pskov or Novgorod in the Russian North, sometime between the late 14th and the middle of the 15th century. In both composition and detail, however, the icon demonstrates the strong influence of Palaiologan art across the Orthodox world.

77.4 x 57 cm

Now in the British Museum, London

(Museum number 1986,0603.1)

Early Safavid Blue & White Charger

At the centre of a verdant landscape, a reclining ibex is craning its neck to pick leaves from an overhanging tree laden with fruit, an imagery symbolic of abundance and fertility in nature. The cresting wave border on the flat rim and the scrolling band of lotus blossoms in the cavetto are directly derived from early Ming blue & white porcelains and testify to the strong influence these wares exerted on Iranian potters a hundred or so years later.

The piece was probably made in the region of Tabriz during the reign of Shāh Ismāil I (1501–24), the founder of the Safavid dynasty and charismatic leader of the mystical Qizilbash / Safaviyya Sufi order established in neighbouring Ardabil a hundred years earlier.

Diameter: 42.6 cm. Height: 10 cm.

Now in the British Museum, London

(Museum number 1982,0805.1)

Comments

This charger provides an excellent illustration of the extent of globalisation many hundreds of years ago, when trade across Asia was flourishing, both overland, via the Silk Road and by sea. The cobalt used by the Chinese potters to decorate their wares was imported from Iran and they called it ‘Mohammedan Blue’. The decorative vocabulary they developed, characterised by sinuous plant forms spreading across the surfaces of objects, was ideally suited for wares intended for export to the Islamic world with its religious and cultural bans on human representation. Indeed, large quantities of exquisite Chinese blue & white wares found their way to the palaces, religious edifices and grand private houses of Istanbul, Ardebil, Damascus, Jerusalem and Cairo.

Unsurprisingly, these Chinese porcelains inspired imitations in Islamic ceramics, of which this charger is an outstanding example. But Iranian, Syrian and Ottoman potters never mastered the technology of firing at the very high temperatures required by porcelain. They used instead a combination of clay, quartz and ground glass which fuses at lower temperatures. So, while they were able to rival and on occasion surpass the originals in quality of decoration, their fritwares (so named after the ground glass, or frit, they contain) are not as durable or impervious to staining as the harder Chinese porcelains.

Large Ottoman tulip candlestick (lâle şamdan)

Cast in brass in three pieces and turned, the flaring shoulder of the bell-shaped base is surmounted by an openwork parapet pierced with a pattern of rumi arabesques. The bulbous baluster shaft is delicately faceted and terminates in a flaring candleholder fashioned like a blossoming tulip with two layers of petals. The lower layer is ribbed and chased with paired leaves inlaid with niello; in the tulip's upper layer, the petals are faceted and at the point they separate to flare outwards, they are delicately engraved with downwards-pointing trefoils.

Height: 53.5 cm. Diameter of base: 25.5 cm

Now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

(Accession number EA1990.1246)

Comments

A metal worker’s tour de force, this candlestick remains to this day the most elaborate and splendid example of this well-known type. It is datable to around the middle of the 16th century during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. To corroborate this date, two marble finials shaped very similarly to the shaft and tulip of this candlestick hang inverted from the muqqarnas over the main door of a mosque in Eyüp, built by the chief architect Sinan between 1551 and 1577 for Zal Mahmud Paşa, a vizier and favourite of Suleiman’s who is remembered primarily for carrying out the Sultan’s order to execute his first-born son, Mustafa in 1553.